Attack Observation: First Honeypot Attack Observation

First Attack Observation Write-up Assignment I created during my ISC Internship

Attack Observation Disclaimer

This post is based on a research assignment completed during my time with the SANS Internet Storm Center internship program. The data represented was collected using a personal Cowrie/DShield honeypot running on a Raspberry Pi CM4. Please note that this observation reflects findings at the time of analysis and may no longer be relevant, since attack vectors and threat actor behaviors evolve rapidly. Any businesses, sources, or indicators mentioned are included as originally observed and should not be considered current or actionable without further verification. This write-up is based on an assignment originally written on September 3rd, 2024.

Threat Actor Introduction

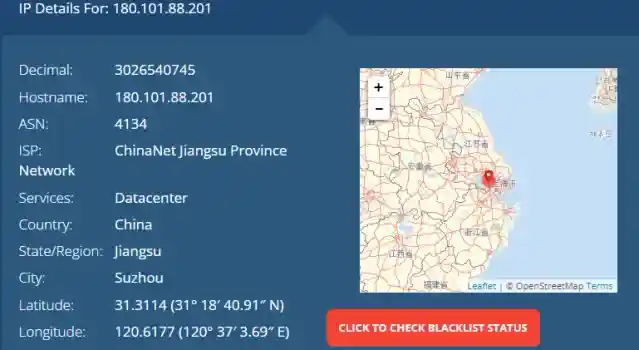

This attack observation will be on a single IP address that accounted for ~17.1% of all recorded activity on the Cowrie logs. The Cowrie JSON logs, between the time range of August 16th, 2024 at 17:00 to August 25th, 2024 at 11:26, included a total of 108,983 Cowrie entries. IP address 180.101.88.201 was logged 17,627 times, that accounts for ~17.1% of the total log entries in that short time frame of just about 10 days. Filtering out all the failed connection logs brought down the total to 13,597 total entries, which is still a very large amount of log entries to exist within this timeframe.

Who is (WHOIS) 180.101.88.201?

The IP 180.101.88.201 originates from a Chinese Datacenter, as seen in the screenshot below:

Threat Actor's Goals?

It seems like one of the primary goals for this attacker was to try to brute-force their way into the system. Out of all the entries that were logged for 180.101.88.201, the only username used in the attack was “root”. No other username was attempted from this source.

I wanted to sort out the logs to find more useful statistics on this attack. I first excluded all session.connect entries and then I also excluded all client.version entries since all those entries were “SSH-2.0-PUTTY”. This left me with 6,758 entries. The remaining entries are:

Failed Login Attempts: 4,027 Attempts

Client.kex Entries: 2,729 Logs

Successful Login Attempts: 2 Attempts

Before I dive into the SSH Key Exchange logs, the successful login attempt entries seemed like a place to look into further. The attacker was able to log in to the “root” user successfully using “Aa123456” and “developer” as the passwords.

Successful Login Attempts

For the first successful login attempt, using the password “Aa123456”, there were a total of 6 logged entries. Unfortunately, the session connection was lost after only 14 seconds. This attacker tried this password three times in total; the first two attempts (on August 17th and 20th) failed, but the third attempt (on August 22nd) succeeded. After this successful login, the attacker did not try this password again.

The story is a bit different for the second successful login attempt, which used the password “developer”. The first attempt with this password, on August 19th, was a successful login, but the connection for this session dropped after only 8 seconds. The attacker then tried to log in with the same password again on August 20th and 21st, but these were failed login attempts.

Closing The Connection After Login?

Following the sessions for both successful login attempts also led to nowhere; all sessions were lost only a few seconds after a successful log in entry. No commands were sent, no attempts at reconnaissance, nothing. This only makes me assume that the attacker was simply doing brute-force attacks to various servers and presumably saving all successful logins to use for future attacks where a compromised host would be needed for any sort of activity the attacker wants to engage in. A compromised host can be used for a variety of things, such as botnets, malicious web hosts, file hosts, and running illicit activities on a clean system/IP. They could also be saving successful login credentials to sell on a marketplace—the possibilities are endless. Unfortunately, not much else can be seen from this attacker other than a simple, automated, brute-force attack on my honeypot.

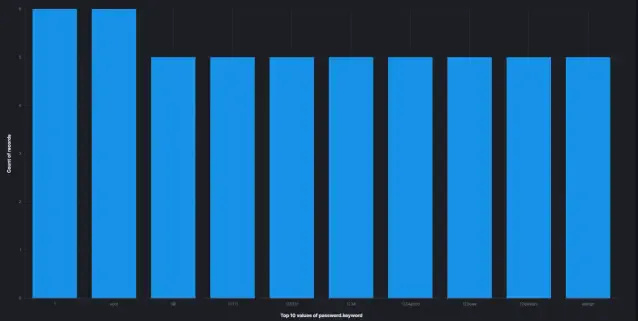

Threat Actor's Top 10 Passwords

Below is the top 10 passwords this attacker used throughout the entire recorded attack:

Understanding The Attack

In regards to the Client.kex logs, we can see a clearer picture on how the attacker operates. Every one of the 2,729 logs have the same hassh value of “1616c6d18e845e7a01168a44591f7a35” which means the same fingerprint was used for all attempts from this attacker. This typically means that the attacker was using the same SSH client configuration in each of their attempts. The same configuration typically highlights an automated script or tool, and an automated script or tool typically aligns with a brute force attack.

There was little to no information present throughout all these logs generated by the attacker that indicated anything other than a brute-force attack. All the sessions were initiated on the same port, 12222, on the honeypot.

Which Vulnerability Was Exploited?

Primary:

-

ATT&CK T1110.001 - Brute Force: The logs indicate that automated brute force activity was present and persistent with all of the attacker’s attempts. This is heavily supported by the same hassh fingerprint value and how the attacker only targeted the username “root” with various different passwords.

-

ATT&CK T1078 - Valid Accounts: The attacker attempted to secure a working password combination for the user “root”. Root is a very common user account on many systems and, in most Linux systems, represents the superuser with elevated permissions. This also further supports the idea that the attacker’s main goal was to only gain working, elevated credentials to systems for future use. No attempts at command and control (C2) or reconnaissance were logged.

-

ATT&CK T1021.004 - Remote Services: SSH: The attacker used Valid Accounts (root) to attempt a successful connection using SSH.

Secondary (Potential):

- ATT&CK T1203 - Exploitation for Client Execution: Through the KEX log entries, we can see that the client system included SSH key exchange algorithms and encryption ciphers that included both modern and known-weak/deprecated algorithms. The inclusion of weaker algorithms could be used as a cryptographic weakness exploit by the attacker.

Threat Actor's Goal (Revisited)

The attacker’s goal appears to be collecting a list of systems that can be compromised and used for illicit activities such as botnets, cryptomining, ransomware, or worms.

By targeting only the “root” username, the attacker was likely seeking systems where elevated access could be gained with minimal effort.

Vulnerability Analysis & Defense

In this attack, the SSH service was vulnerable as it allowed for repeated brute-force attacks from the same source.

SSH Vulnerability Defense

The most important step that should have been set up when the system was first initialized was to ensure that root user log in could not be done over SSH. Enabling root user log in via SSH introduces a severe weakness to the system and makes it an ideal candidate for attacks such as this.

The second step that should have been considered would have been to use SSH keys rather than passwords. SSH keys make brute-force attacks virtually impossible, as the only method for SSH log in would have been to use a private SSH key instead of guessing passwords.

To defend against this type of attack, consider the following best practices:

- Disable root user logins over SSH.

- Use SSH keys instead of passwords for authentication.

- Implement rate limiting and connection throttling on the system or firewall.

- Enforce strong password policies.

- Block known malicious IPs from accessing your network or specific ports.

- Use non-standard SSH ports (though determined attackers may still find them).

- Deploy an intrusion detection system (IDS) to monitor for suspicious SSH activity.

- Enable account lockouts to slow down brute-force attempts.

Threat Actor Details

The attacker, 180.101.88.201, originates from a Chinese Datacenter. The IP address has been reported many times to the Internet Storm Center.

Indicators

-

IP: 180.101.88.201

-

SSH Fingerprint Hash: 1616c6d18e845e7a01168a44591f7a35